Are You Overfitting Your Wires? A look at breast root anatomy

Bra making has taken a very modular turn in the past few years: to make a well fitting bra, you must:

- Take a root trace (while leaning forwards)

- Match this to a wire chart and order some similar wires

- Make a fitting band to fit your wire and band

- Add the cups and fit those

This system works well for some, but there are some pitfalls that are very easy to get muddled in when approaching bra making like this. Beginners especially can sometimes be lost in endless alterations, a lack of lift, and perpetually uncomfortable bras. These issues stem largely from the ideas that:

- The best fitting wire is one that matches your root width perfectly

- The wire must fit close to perfectly for the bra to fit well

- A perfectly taken root trace (again, taken leaning forwards) will show your breast root perfectly

- The fit of the wire can - and should - be determined without adding the cups, to avoid tissue being pushed out by too small cups

- The cups can then be easily altered to fit with this new frame

I believe that all five of these are essentially incorrect, and certain people struggle more with their bra fit because of these beliefs. The biggest impact is for large cupped people who wear multiple wire sizes smaller than their volume suggests (a projected shape, also sometimes erroneously called omega). Those who wear larger wires than their volume suggests usually have more success in their fitting in comparison, especially those with self breasts, and are not the main focus of this post.

An extended version of this post can be found on my Ko-fi,

where you can get instant access to this and previous extended blog

posts for just £2/$3. If you want, you can then continue subscribing on a

monthly basis to support my blog.

Why does wire size even matter?

I'm not a total heretic: I agree fully that a perfectly fitting wire is one that surrounds the breast root, matching in height, width, and overall shape when worn.

A wire that is too wide causes a gap between the side of the breast and the edge of the cups. An excessively wide wire can wrap around the rib cage and sit at an uncomfortable point. A wire that's only slightly too wide may cause some instability within the cups, but typically it's not very much and can usually be reduced by cup shape alterations.

A wire that is too tall also causes a gap between breast and chest - usually it sits too low on the body, causing space at the bottom of the cup. This is usually more unstable than a too wide wire because the bottom of the breast needs more support than the side. A wire that sits below the breast root can dig into the stomach/ribs as well. Aesthetically, space between the wire and breast can cause wrinkles and creases in the cup fabric.

A wire that is too narrow often sits on breast tissue, which can

cause pain and possible injury, in addition to tissue slipping out of

the cups. It may not sit on tissue though, instead, the breast may push

the wire downwards, making it sit too low. In cases where the breast is

particularly heavy/firm, the breast itself can

deform the wire, causing it to spring open too far, or dig into the

chest. When a too narrow wire is pushed down, there will either be a space between the wire and the bottom of the breast, or the breast itself will no longer be lifted away from the chest. The issues of digging and cup fit issues may also appear.

A wire that is too short When

a wire is too short to contain tissue, the wire can again be pushed down by

breast tissue spilling out the top. A too tall wire, on the other hand,

usually manifests as sitting low on the torso. It may dig in at the

armpits too, but usually people position a wire lower down to where it

feels comfortable.

Unfortunately, since wires themselves come in set sizes, growing in both

height and width (while maintaining a set overall shape and usually

gauge), compromises must often be made between matching the root height

and the root width. Gore height is another compounding factor, which

won't be discussed in this post, so by height I am mostly referring to

the height of the armpit wire tip. Wire shape and gauge are two further

variables that aren't discussed here.

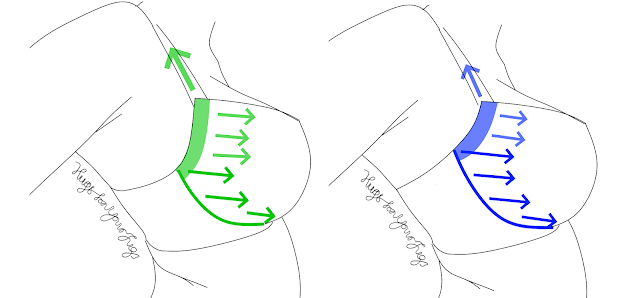

Wire height is crucial for large bust support

|

A short wire causes more force to be put on the strap than a taller one. |

Typically when someone large busted has a narrow breast root, they are advised to size down in the wire - the wire will appear to fit the breast root better. However, when we size down in width we size down in height as well, and this can lead to major support issues within a bra.

The underwire is key in a wired bra - it provides rigidity to the frame, allowing the cup to project outwards. It forms a point of resistance to both the horizontal and vertical forces of the breast, transferring them to the band. Think of the wire as an anchoring point for the cup fabric to attach to.

The

region of the cup that connects the wire to the strap is much less rigid than the wire and thus

less able to support the breast, relying on the tension between strap and wire (helped by the band) to support the cup fabric and contain tissue.

If the wire is short, the required tension can be significant, putting excess strain on the strap. Not only does more of the cup fabric (and thus more breast tissue) need to be supported by this region, but more of the breast itself needs to be contained by this fabric to stop it slipping out of the cups.

Also consider the profile of the bust. When a bra lifts breasts, it pushes inwards on them to create that rounded upper shape - pushing in most at the apex. The bra therefore needs to be strong at the apex level to maintain that inwards tension. At the apex level, the breast mass is held furthest from the chest, increasing the moment on the wire at this point. Generally speaking, it's very hard to maintain the bust apex of a large breast above the wire tip, and for very large breasts even this position can be difficult.

This is why maximising the wire height under the arm is so important. In my experience, a wire that is too wide does not cause significant problems - side support can be utilised to help keep tissue out of the armpit - but one that is too short can make it very difficult to build support into your bra cup. This is why, when compromising between width and height, I always recommend keeping height. But are these compromises as common as we believe?

Large breasts, root width underestimation, and why you shouldn't lean forwards to determine your root.

Breast

roots are tricky things. It's easy to find the inframammary fold, and

the root near the gore, but everything seems to go a bit pear shaped

when finding the root at the side. You're not alone in this difficulty - breast anatomy itself is what makes this tough.

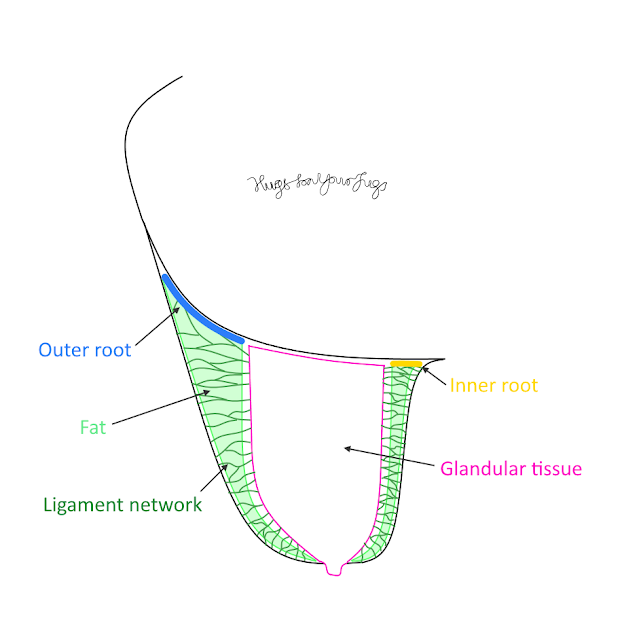

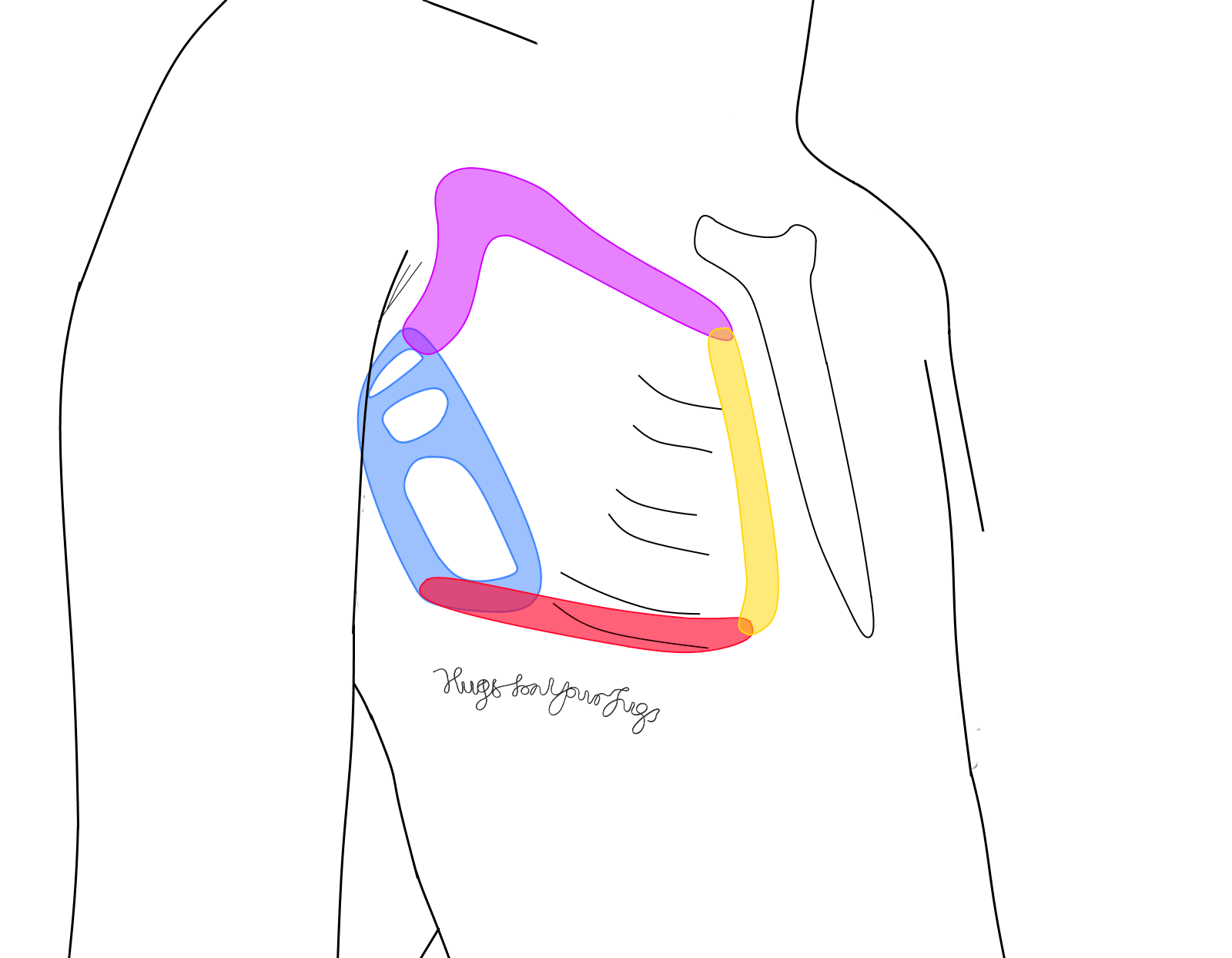

|

| Typical breast root size and location, adapted from a dissection image. Each colour represents a differently structured area of the root. |

While the root is quite literally a fixed ring, the breast itself is flexible. The breast tissue itself has a complex internal support structure (the Cooper's ligaments) that goes from the rigid chest wall to near the flexible skin, directly through the tissue. The breast itself has multiple regions too: the tissue directly above the root is fatty and contains those supportive ligaments, and the glands that produce milk remain entirely within the circle of the root. This fatty tissue domes over the glandular tissue, forming a capsule that thins out until it reaches the nipple. There's a thin layer of fascia under the skin that anchors the ligaments that pass through the fatty layer. As the Cooper's ligaments are flexible and the skin is movable, the breast capsule and the surrounding fatty layer can change in shape, stretch, move, bounce, all the things we use sports bras to stop.

You probably know from experience that the

root at the sternum is well defined, strong ligaments here attach the capsule directly to your ribs. The inframammary fold is also easy to

spot, containing horizontal ligaments that form a solid crease. These roots are concentrated over a small area, and are both located on the front of your rib

cage, so lifting your breasts (or leaning forwards) will reveal them

quite easily.

The breast root at the armpit side (the lateral

root), is more difficult. It has fewer and weaker ligaments that take up

a larger area on your rib cage, and is also located more at the side,

where your rib cage becomes curved. It also attaches to the fascia over

your muscles, rather than the bone. For what it's worth, the root at the top of the breast is similar which can make root height hard to determine.

|

| Leaning forwards can obscure the lateral root due to its low density and location on the side of the ribs |

When you lean forwards, the

breast capsule is pulled forwards by gravity, and the tissue inside

lengthens. The weaker ligaments at the lateral root will stretch and

allow for the capsule to move away from the root and down your rib cage,

possibly quite substantially.

If you prod around while leaning forwards and feel your

lateral root, it may well feel like nothing - there's no glandular tissue

here, just this thinly concentrated ligament structure. What's more is that because the

root here is attached to muscle, if your muscles are deformed/pulled

slightly by the weight of your breasts, your root itself may be

artificially narrowed. If you're using wire or otherwise manipulating your tissue when trying to find your root, you can end up pulling the fatty layer even further towards your sternum, stretching out your root ligaments more and making your breast appear even narrower.

So leaning forwards could well give you the idea that your breast root is a lot smaller than it actually is. You may also come up with a bit of a strange shape too, depending on how your breast moves. Those with larger and less self supporting breasts are more likely to experience this, for obvious reasons.

Your root isn't static with breast/body size either - having more body fat in this area causes the root itself to widen, as fat pockets sit between the fibres that make up the ligaments, making the attachment points sit over a larger area. This explains how with weight or breast size increase, you will usually need to size up in the wire. This shouldn't come as a surprise, given that wire sizes increase with both cup and band size, but some people claim that your breast root is determined solely by your skeleton/musculature, which isn't the case.

|

| The perils of a too narrow wire |

If you decide to go for a wire based on this narrowed root, sure, you could perhaps wear a wire over

these ligaments without too much discomfort, but in doing so these

ligaments will remain stretched, which to me seems antithetical to the

purpose of a bra. Besides, when a bra performs that compressive lift

that we talked about earlier, the capsule will necessarily spread back

to the side. This is why some people (including me in the past lmao)

claim the root widens in a bra - it really only appears to widen.

Putting a wire on top of these ligaments that are being simultaneously

stretched (by the wire) and relaxed (by breast compression) doesn't feel

like a very good system to me, and also will probably be quite

unstable, as you are cutting off the natural containment system of the

breast, the root. What's more is that your breast may fight against the wire, overspringing it, pushing the bra down, or slipping out underneath, due to this wire likely being both too narrow and too short.

|

| An easier and more accurate way of determining your root - the lift and push |

In my opinion, a better system for determining the root than leaning forwards is an older one, popular in bra fitting circles. Lift your breast and push it back against your rib cage, and use your fingers to determine the extent of your fibrous/sensitive tissue. The lateral root will stop your tissue moving further back, giving away its location.

Are fitting bands and omega alterations muddying the water?

It's

often suggested to test your wire fit by using a fitting band - an

entirely cupless bra. For less self supporting breasts, even standing

upright can distort the appearance of the root for similar reasons to

the ones above - it may appear narrower and shorter than it actually is.

You may also have a skin fold that can be mistaken for the breast root,

which usually disappears with full support. Furthermore, wires can feel

very uncomfortable without cups, as they will sit a lot more firmly

against your chest, and can interact with that skin fold in a painful way.

I fully support the use of a fitting band to be able to test out different cups, but checking wire and band fit from a cupless band can cause lots of problems.

Another issue with this fitting band first

method is that you determine your wire size, but then you must alter your bra pattern to fit the wire. If

you do this using the omega alteration, you are introducing unintended changes to the cup geometry of your bra, such as: the neckline

proportionally becoming very long in comparison to the opening of the

wire, changes to the curvature in the cup pieces, changes to the angles at which they hit the seamline. If you are new to bra making, and especially if you don't already

have a well fitting bra, these fit issues can be hard to diagnose and

you may end up believing that your resulting unsupported, east-west pointing breasts

need a narrower wire. You can absolutely bog yourself down in a cycle

of unsupportive bras to fitting bands to new wires back to unsupportive

bra again. Why not remove one factor from the equation and get the cups

and band fitting well first, then focus on the fit of the wires?

In the extended edition of this post, I talk more about my personal philosophy of wire fitting and why I rank it much lower in importance than other aspects of fit.

If you liked this post, be sure to follow me for email updates whenever I post a new one! If you really liked this post, donate to my Ko-fi for extra content!

Bibliography

Apologies for no proper citations, but my references for breast root anatomy can be found here. Feel free to leave a comment if you're having trouble sourcing my claims. CW: images and footage of dissection.

McGhee, D. E., & Steele, J. R. (2020). Breast biomechanics: What do we really know?. Physiology, 35(2), 144-156. (This is great btw has tons of interesting stuff in it)

Thank you. Your articles always makes me think

ReplyDeleteThis is very interesting. Thanks.

ReplyDelete