Bra Physics Part 3: What can we learn about the wires and cradle?

This is Part 3 of my Bra Physics series. In Part 1, I described the forces involved in supporting your breasts and what parts of a bra are responsible for providing those forces. In Part 2 I introduced the concepts of stress and strain, and applied these and part 1's principles to the design and fit of bands. Now let's move on to the much maligned underwire (and the cradle).

In the original Bra Physics post, I didn't talk much about the role of the underwire. The

wires are a critical part of the "foundation" of a wired bra, as

improper design or fit can cause pain and even injury, as well as reduce

the support available in a bra. The underwire's main job is to resist the forces of the band, maintaining a cupped shape despite the bra being under high degrees of tension. Because the underwire is being pulled on by the band, we need to recap the stress and strain concepts discussed in Part 2.

Recap: Stress and Strain

The

strain of an item is essentially how much its length has increased, as

a proportion of its original length. If your bra band measures 30" on

the table, and you put it around your 33" underbust, you have created a

strain in the fabric of 3/30 = 0.1 (strain has no units). If we strain

a material a little bit, the deformation (ie change in length) is

elastic and thus reverses as soon as we stop applying force. If we

strain it too much, the deformation becomes plastic and the material is

permanently deformed.

The

stress within an item is related to the force that you put on it.

Stress is a quantity within a material that occurs when you transmit a

force through that material. Stress is defined as the force transmitted

through a surface divided by its area. The same force over a smaller area equals greater stress.

High stresses in a material reduce their longevity, and high stresses upon the body can cause pain and injury.

Wire Size and Firmness

As discussed in Part 1, wires

should fit just around the breast to ensure they are not sitting on

moveable, sensitive breast tissue, and do not leave extra space for the

breast to move around within the bra, keeping tension in the fabric in all parts of the cup. Wires that are too small or short

can also cause breast tissue to spill out of the top at the armpit, pushing the entire

bra downwards.

A

taller wire, while potentially uncomfortable, supports the fabric in

the cup better and means that less support from the strap is required.

This is why, as mentioned in Part 1, strapless bras nearly all have

quite tall wires - more of the upper cup is supported. For the best support and lift, go with the tallest wire that you can comfortably wear - but be warned that wires that are too tall have a tendencey to sit below the inframammary fold.

Wires

are typically steel, and range in spec from very firm to very soft and

flexible. An appropriate wire for any one person has to balance firmness

with flex - both qualities are useful but everyone's personal needs are

different.

A

firmer wire exerts more pressure on the body, and does not widen much

when the band is stretched (this widening is called wire spring). This firmness carries the tension of the band through the wire, holding it securely against your body across the wire's entire area. This increases the friction at the wire and thus the support of the bra. However, a firm wire's inability to conform to your shape may cause pressure

points or discomfort when wrapping around the body. The most common

pressure points are at the bottom of the wire and at the gore and armpit. The pain at the bottom of the wire is because the wire is not wrapping smoothly around your body. The pain at the tips is because the arms of the wire are not conforming well to your torso shape. Pain in these places may be alleviated by a softer, more flexible wire - but not always.

|

| A too soft wire can be pushed outwards by your breasts, causing floating at the gore and armpits and digging at the bottom of the cups |

A

more flexible

wire springs more when worn, and also more easily bends in the

front-to-back plane to

wrap fully around the body. These qualities make a softer wire more

useful for round rib cages, wider breast roots, as well as for those looking for more

comfort. A more flexible wire has a higher tendency to float at the gore

and even stick out at the armpits

as it is less able to resist the force the breasts exert on it.

Additionally, a wire that is too flexible may not distribute forces

across the wire's surface as much. This floating can cause the entire bra to tilt forwards and dig in at the bottom of the wire.

Wire Bending, Fatigue and the Usefulness of Spring

Some

people like to bend their wires to help them fit around their bodies

better. Bra drafters often have different ideas about how much spring to

add into their cradle designs, which can affect how much the wire

springs when worn. I won't go into either of those topics here as this

post will be too long, but suffice it to say that a bra's design and

additional modifications can be used to improve the comfort and fit of a

wire.

Whenever a bra is worn the underwire undergoes some degree of elastic

deformation - the "spring" in spring. Although the wire can return back

to its original shape (the "elastic" in elastic deformation), repeated

applications of force cause it to undergo fatigue. Fatigue causes microscopic cracks and tears in materials, which then grow due to repeated loading and unloading. The greater the force

applied, the greater the effect of the fatigue; this fatigue is the

cause of wires breaking over time. Fatigue also causes the threads on the wire

channelling to weaken and allow the wires to poke through. Overly snug

bands spring the wires more, putting higher overall forces on the wire and cause them to fatigue more quickly.

However, the cause of most wire breakages and wires poking through is, in my experience, most often related to boob hats, which are bras that are not held firmly against the body. I suspect this is due

to increased movement during wear causing more loading cycles (and thus speeding up fatigue), as well

as floating gores causing a greater concentration of stress at the

bottom of the wire.

In addition to increased fatigue, overstretching the band will overpower the rigidity of the underwires,

springing the wires wider than intended and reducing the projection of

the bra which is why it can be tough to tell you're wearing a parachute bra. If

you want a highly projected or narrow bra, choosing a firm wire will

allow the band to hold the cradle tight against your body and not let

the cups be pulled wider and flatter.

Is tacking really all that important?

"Tacking"

is the term used to describe when the gore of a bra (the part where the

wires come together in the middle) lies flat against your chest. A

tacking gore is desirable because it ensures that your breasts are fully

separated and the centre front of the bra is in full contact with the

skin, which improves support in two ways - plus, it's the only support structure in the centre front of a bra.

A

tacking gore is important because it ensures the breasts are fully

encased within the bra, maintaining cup tension on the inner half of

the breasts and allowing this area to be fully supported too. Keeping the

centre front of the bra in full contact with the torso is also important as the gore of a

bra provides important friction to provide some upwards force and keep

the bra stable.

A

floating gore, on the other hand, does not maintain tension on the inner half of the cups, reducing that all-important inwards force a bra needs to provide to lift your breasts. Additionally, a floating gore can cause the whole bra to tilt forwards and dig in below the breasts, as well as sliding down at the front due to a lack of friction.

While

some breasts are too closely set to fit even the narrowest gore between

them, getting one as closely tacking as possible makes a huge

difference in the support and security a bra is able to provide as it keeps the inner half of the cups under more tension.

Designing the Cradle

The cradle is the fabric that directly surrounds the wire in a bra, attaching to the band at the side seams.

A wider cradle (i.e. a taller one) made out of a low stretch fabric will both keep a high

band tension and keep the wires in place.

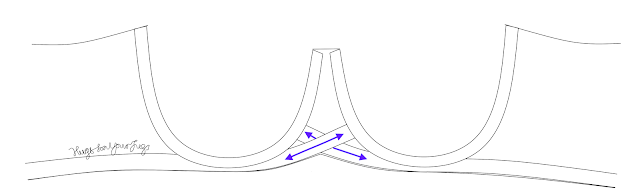

The elastic attaching to the lower edge of the cradle is strong and can reinforce the section below the cups, reducing distortion of the lower gore. Another option for strengthening this area is to use a Gothic Arch. Gothic

arches are two strips of under cup elastic which cross over each ther and attach directly to the inner gore. This construction technique

can also be used to improve comfort as it sits higher than a traditional full band.

What about Cradle-less ("Partial Band") Bras?

You can see the extended version of this post for a short analysis (I don't want to oversell - it's legit 1 paragraph) on these, which touches on concepts only discussed in the extended version of Part 1 of this series. You can read all extended versions of my blog posts for just £2 on my Ko-fi, and make a monthly pledge to continue supporting my blog if you want!

If you liked this post, be sure to follow me for email updates whenever I post a new one! If you really liked this post, donate to my Ko-fi for extra content!

This is Part 3 of my Bra Physics series. In

This is Part 3 of my Bra Physics series. In

Comments

Post a Comment